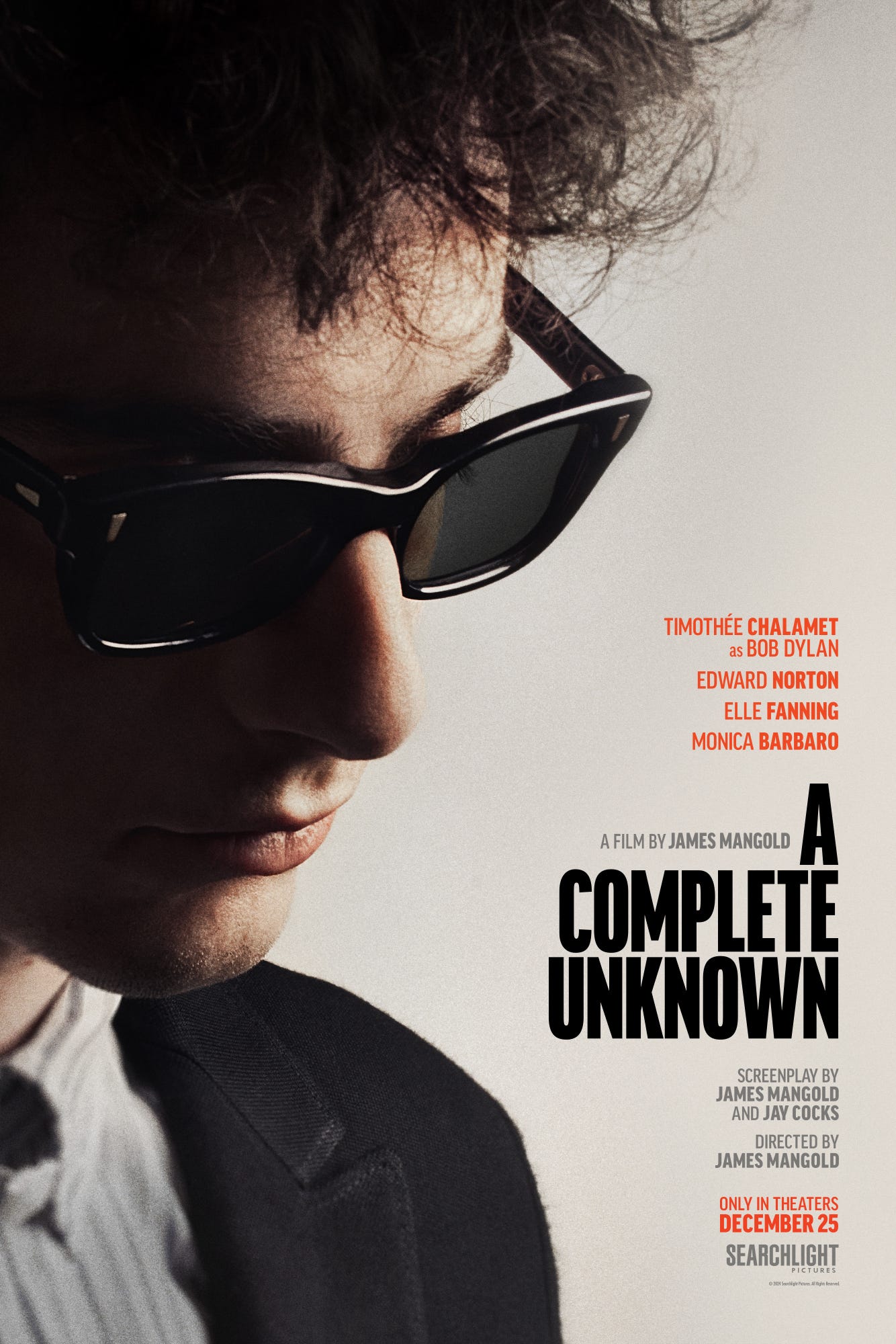

REVIEW: A Complete Unknown

Chalamet shines as iconic singer is put into historical context.

Your answer is right there in the title.

If you’re looking to at long last figure out the enigma that is Bob Dylan, Director James Mangold’s A Complete Unknown ain’t what you’re looking for, babe.

Especially in his early years, Dylan wove himself a coat of contradictions, not just changing his last name from Zimmerman, but inventing an entire backstory out of whole cloth. He’d make up stories about his life not just for reporters but for those closest to him — obscuring what was a somewhat nondescript childhood in Minnesota.

Mangold picks up his story with Dylan arriving in New York city in 1961, and logically ends it with his controversial decision to “go electric” at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival. As biopics go, this is a pretty conventional structure, one Mangold has already mastered with his Johnny and June Cash film Walk the Line. But, just because it’s rooted in convention doesn’t mean it’s not a top-notch film on every level.

It’s amazing how far good films have come in the last decade or so when it comes to defining a time and place. Movies set in an earlier period used to be filmed in generic Hollywood backlots using gleaming cars of the era that all looked like they just came from a collector’s showroom — which they did. Mangold and his set and art direction teams do a fantastic job putting the audience in the gritty lower east side, the beating heart of the burgeoning folk scene. You can almost smell the dirty ashtrays littering the basement folk clubs and dingy apartments where Dylan quickly develops a following after making a hospital pilgrimage to meet his hero Woody Guthrie and finds an advocate in purist folk ambassador Pete Seeger.

At the “marketing” heart of the film is a love triangle between Dylan and artist/activist Sylvie Russo (Elle Fanning) and folk “it” girl Joan Baez (Monica Barbaro) who are both tangled up in Dylan’s freewheeling love and professional life. Mangold wisely avoids the TV movie clichés of the triangle because the reality of Dylan’s intentions seem much more fluid.

Sylvie may be a muse, but she feels like the titular Girl from the North Country who is destined to be a woman who once was a true love of mine. The relationship with Baez seems equally doomed, a mix of mutual admiration, exploitation, and distain.

After releasing his first album of almost all cover songs that fails to catch fire, it’s Baez who brings Dylan to the masses with her own covers of his originals. As his star rises and he weaves between the two women the true heart of Mangold’s film is revealed: Dylan’s critical role in the larger musical and cultural context of history.

The birth of rock and roll in the mid-1950s was a lightning bolt in popular culture. Elvis, Jerry Lee Lewis and Little Richard changed the musical landscape. But, by 1961 the sharp edges of rock had been dulled. Presley was making sappy Hollywood musicals and the charts were dominated by finger-snapping crooners that seemed more akin to the Frank Sinatra era. It was almost like rock and roll had never happened.

In the broad-brush sweep of music history, it’s The Beatles who relit the fuse and brought rock back for good. Mangold seems to be putting a spotlight on Dylan’s role in that history. It’s established early on that Dylan is no folk purist. He knows and appreciates Little Richard B-sides, and once The Beatles hit, it’s clear that he’s not going to allow himself to be pigeon-holed into one genre — setting up the conflict of the last act of the film.

From acoustic to electric what has always set Dylan apart are the lyrics, which Mangold puts front and center. Singing those lyrics (and playing Dylan in general) is the make or break performance of the film, and Timothée Chalamet is more than up to that herculean task.

Chalamet is rightfully considered one of the best actors of his generation. But, when he was announced as the lead, some people may have been leery of him for the role. He is, after all, considered a sex symbol to many. But, seeing him as Dylan reminds one that his physical appeal isn’t rooted in a traditional “matinee idol” look. And while he may not be a ringer for Dylan, he fully inhabits the man.

The heart of the performance is beyond the physical. Dylan has been a cultural staple for generations now — his speaking and singing style caricatured by countless comedians. Chalamet could have easily fallen into impression, but it never feels that way. Playing and singing all the songs live is a revelation. The actor sings at a slightly lower register than Dylan, and Chalamet takes some of the nasally edge off the Dylan originals. Not only does that minimize the “impression” but, arguably, makes the lyrics stand out even more.

And what lyrics.

The songs tumbling out of Dylan’s brain during this time were simply revolutionary — protest poems that captured the zeitgeist of a new generation and aching love songs that elevated the form to levels never before achieved. Watching them being born in the broader context that Mangold establishes gives them a whole new life and even deeper relevance and feeling.

All of the supporting cast shine when put in the spotlight. Beyond Fanning and Barbaro, Ed Norton is fantastic as the sympathetic Seeger, and Boyd Holbrook’s Johnny Cash demands attention in every scene he’s in. But, Chalamet is the obvious center pole holding up the circus tent. It would be a sin if he’s not nominated for best actor.

Chalamet isn’t the first actor to play Dylan. Todd Haynes’ 2007 film I’m Not There enlisted six different actors (male and female) in an attempt to get to the core of the enigmatic singer and ended up simply coming up with the same answer — that Dylan contains multitudes.Mangold’s A Complete Unknown (a phrase nicked from Like a Rolling Stone) might not take as big a swing, but it still hits.

Like the lyric preceding the title, Mangold seems to be asking how does it feel?

The answer to that one is easy: Damn good.